Bioburden Bible: Identifying and Reprocessing Human Bioburden in Instrument Reprocessing

This program is approved for .5 CE credits through HSPA. To receive your credits, you must earn an 80% passing score on the quiz at the bottom of this Report.

Objectives:

- Define the types of bioburden SPD and GI departments are responsible for removing from medical devices.

- Explain how enzymes interact with bioburden to aid in the denaturing of organic compounds to facilitate cleaning.

- Analyze the types of enzymes used in medical device reprocessing

Sterile processing and gastroenterology professionals are asked to move mountains daily. From manually cleaning thousands of instruments to hauling heavy trays of devices, and quality checking every step along the way, they go through great means to ensure safe and clean devices for their patients.

Sterile processing and GI however are often reduced to the hospital ‘dishwashers’; cleaning, brushing, loading and processing thousands of devices a day to keep operations running. Such an oversimplified description fails to capture all the nuances of effective instrument reprocessing.

One such area is that human ‘bioburden’ is uniquely different from other forms of ‘dirt’ and ‘debris’. Its unique characteristics require sterile processing and GI to adapt cleaning processes and tools to tackle these forms. Let’s evaluate these unique bioburden categories, and how they might impact how and why instrument reprocessing is unique.

Bioburden

Bioburden is defined as “the number of contaminated organisms found in a given amount of material before undergoing a sterilizing

procedure” by the Patient Safety Authority1. For the purposes of this overview, two major categories of bioburden are dis

cussed. Each of these two groups have unique properties which may require unique cleaning practices:

- Protein-based bioburdens

- Fat-based bioburdens

Protein-based bioburden

Proteins are complex, highly structured molecules which provide the body with a variety of critical functions. We rely on proteins to keep us alive3. Blood is a common

protein-based bioburden cleaned in sterile processing and GI. Collagen is also a protein, which makes up the body’s skin, tones, tendons, and ligaments. Protein is a major structural component in the body made up of folded chains of amino acids and make up our cells and tissues, as well as many enzymes and hormones.

protein-based bioburden cleaned in sterile processing and GI. Collagen is also a protein, which makes up the body’s skin, tones, tendons, and ligaments. Protein is a major structural component in the body made up of folded chains of amino acids and make up our cells and tissues, as well as many enzymes and hormones.

Denaturation, which modifies the structure of the protein to break up its bonds, causes them to have a looser structure and sometimes insoluble quality. High alkaline or acidic properties, heat, or certain detergents can all cause denaturation, making cleaning protein-based bioburden more difficult. For protein-based bioburdens, such as blood, this often results in coagulation and the formation of biofilm.

Fat-based bioburden

Lipids are a diverse group of organic compounds that include oils, fats, hormones, and certain compounds of membranes that group together because of their aversion with water4. Lipids help the body store energy, absorb nutrients, and create hormones. Lipids may be discovered on orthopedic devices for their prevalence around joints5 as well as plastic surgery devices that routinely come in contact with skin, oils and fats during grafting and reconstruction. Fat ‘pads’ many parts of the body to protect and insulate.

Lipids are notoriously hydrophobic, avoiding interactions with water, and often stick together as insoluble masses. That quality can make reprocessing particularly tricky.

Carbohydrates, such as glycogen, act as a storage compound in the liver and muscles6. The human body has little structural carbohydrates, and therefore, isn’t included in this overview as a unique category.

Other types of bioburdens

The human body is composed of many chemicals, minerals, and organic compounds. These chemicals come together to configure unique forms of human bioburden we see in instrument reprocessing, and are usually a combination of proteins, fats, minerals, and other organic compounds. Some of these might include:

- Bone is made of protein, collagen and minerals such as calcium, so while not its own type of organic bioburden, is prevalent after some medical procedures.

- Feces, while also prevalent in lumens found on some GI flexible endoscopes, is also not a unique form of organic bioburden, but mostly made up of indigestible matter like cellulose, cholesterol, fats, water, and dead bacteria.

Sterile processing and gastroenterology professionals should be cognizant of what forms of human bioburdens they may encounter in reprocessing. That knowledge can help implement cleaning tools and technologies to tackle these bioburdens.

The Role of Cleaning Chemistries

Enzymes are biological kick-starters. They already exist in the human body and help facilitate chemical reactions by binding to substrates to lower the threshold necessary to create a reaction. Enzymes are at work in the stomach, breaking down complex molecules into simpler forms to help digestion, or in the liver breaking down toxins in the body.

Enzymes are also found in enzymatic detergents, and are often categorized into groups:

- Protease, which targets protein-based bioburdens such as blood and feces.

- Lipase, which targets lipids and fats. Lipase can help counter the hydrophobic properties of lipid compounds and make them easier to break down and clean.

- Amylase, which targets starches.

Enzymatic chemistries play a critical role in manual and automated cleaning efficacy both in SPD and GI reprocessing. Though some enzymatic detergents have single enzyme properties, there are multi-enzyme chemistries on the market. It is crucial to follow manufacture IFU on water/solution temperatures to ensure proper activation of the enzymes to aid in the cleaning process.

The Role of Technology & Processes

Technology is evolving at a rapid clip, most certainly in endoscopy and sterile processing. It’s both fun and fascinating to watch the investments in new washer-disinfector, ultrasonic, manual cleaning, quality assurance (ie cleaning verification & visual inspection), and sterilization technologies being developed.

SPD and GI departments have responsibilities to constantly re-evaluate their technological arsenal. As surgical devices become more

difficult to clean, so then must the technology evolve to clean them.

difficult to clean, so then must the technology evolve to clean them.

If new technology isn’t attainable, process updates can alleviate some of the challenges. This can include reviewing chemistry, equipment and instrument IFUs for improved or updated steps such as soak times, water temperature, brushing techniques or flushing requirements . Evaluate what processes are being conducted in a department and evaluate which have failed to change over the past 2-5 years. Manual cleaning, quality assurance, and sometimes visual inspection are areas which require new methods and practices.

Importance of Point-of-Use Cleaning

All medical device reprocessing begins immediately after the surgical procedure. Point-of-use cleaning is incredibly effective and important in the immediate breakdown of debris and bioburdens. Doing so immediately prevents the formation of biofilms. Collaboration with the operation room starts the foundation for effective point-of-use practices.

“Biofilm consists of an accumulated biomass of bacteria and extracellular material that is tightly adhered to a surface and cannot be removed easily. Biofilm has the effect of protecting microorganisms from attempts to remove them by ordinary cleaning methods used in the sterile processing area and of preventing antimicrobial agents, such as sterilants, disinfectants, and antibiotics, from reaching the microbial cells.”

|

Central sterile and endoscopy professionals are tasked with many challenges, some of which include processing of human bioburden and organic compounds. These bioburdens are far different than other bioburdens that are cleaned or reprocessed in other areas. One in that their make-up and characteristics require unique cleaning practices. Secondly, in their ability to harbor dangerous microorganisms which can cause harm to both medical staff and patients.

Endoscopy and sterile processing professionals can evaluate these four factors to ensure they’re equipped with the arsenal to tackle these unique bioburden challenges.

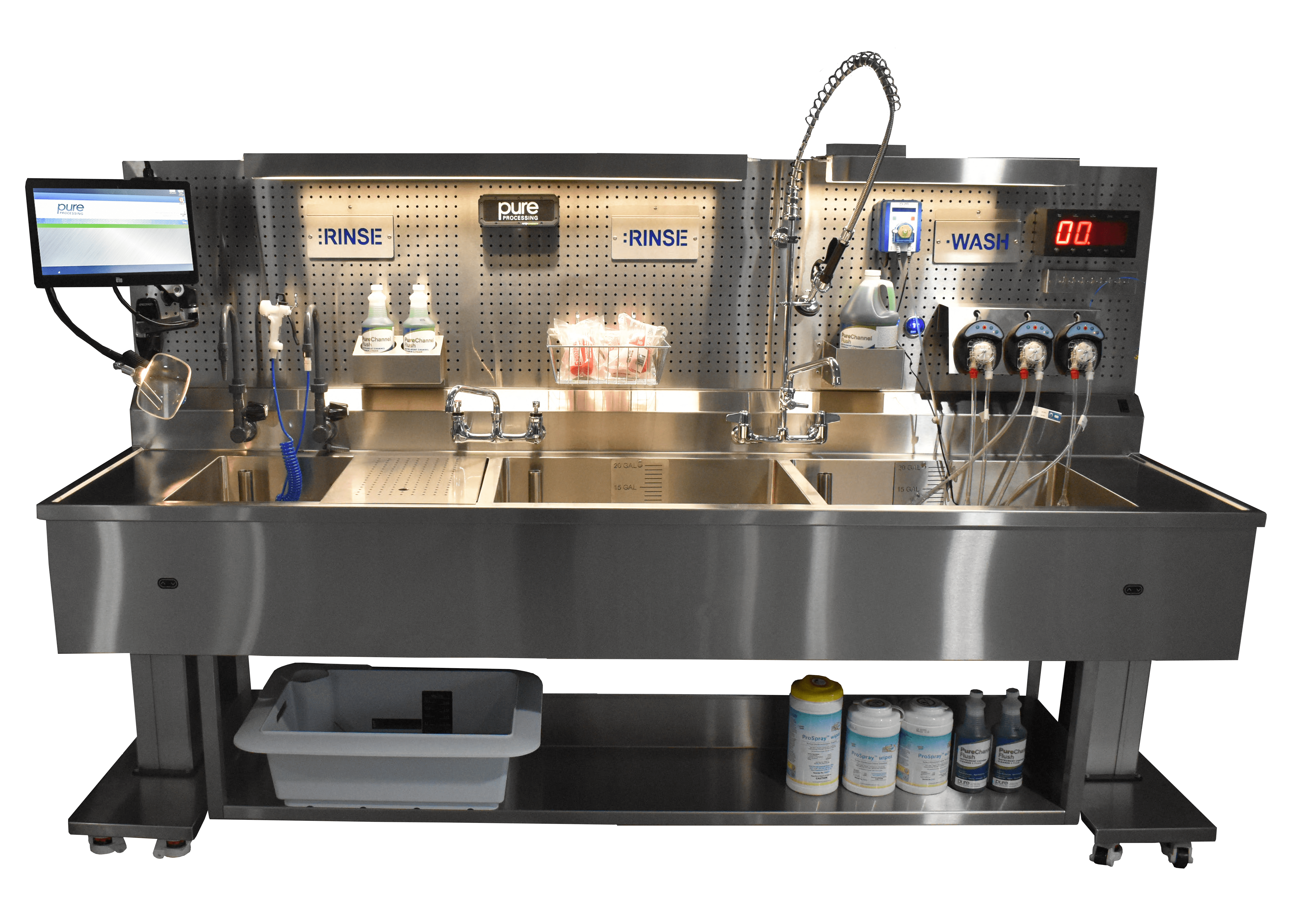

Looking for ways to improve your sterile processing or gastroenterology cleaning processes? Learn more about how the FlexiPump™ Independent Flushing System helps departments tackle their toughest instrumentation & cases!

Works Cited

- Authority, P. P. S. (n.d.). Bioburden on Surgical Instruments | Advisory. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority. https://patientsafety.pa.gov/ADVISORIES/Pages/200603_20.aspx

- FS14/FS077: Basic elements of equipment cleaning and sanitizing in food processing and handling operations. (n.d.). Ask IFAS – Powered by EDIS. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/FS077

- National Human Genome Research Institute. (n.d.). Protein. Genome.gov. https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Protein

- Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2024, March 27). Lipid. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/lipid

- Daigle, P. (2022, November 4). Your guide to enzymatic cleaners. Outpatient Surgery Magazine. https://www.aorn.org/outpatient-surgery/article/2016-January-your-guide-to-enzymatic-cleaners

- The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, May 16). Human body | Organs, Systems, Structure, Diagram, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/human-body