The F-B-C’s of Clean: Manual Cleaning Foundations in Instrument Reprocessing

Manual cleaning is the foundation for all reprocessing activities that follow. Whether it’s ultrasonic cleaning, automated washing, or high-level disinfection and sterilization, every subsequent step relies on the effectiveness of manual cleaning. Ultrasonic cleaners may help with complex instruments, but they cannot remove bulk bioburden. Automated washers and thermal disinfection units also depend on instruments being free of residual soils for their processes to be effective.

Look no further than a recent 2024 study by Ofstead and Associates to realize the critical importance of manual cleaning. In this study, borescope examinations of ten suctions and eight different shavers demonstrated that 94% of the instruments had visible debris or discoloration within their lumens. Researchers even documented retained soil and brush bristles in several new shavers, despite following manufacturer instructions for cleaning, and found visible damage and discoloration within just five uses. These findings underscore that even with modern tools and training, cleaning outcomes require ongoing attention, consistency, and process improvement.

Industry standards reinforce this reality. As stated in ANSI/AAMI ST79:

“The first and most important step in reprocessing reusable medical devices is thorough cleaning and rinsing. Cleaning removes microorganisms and other organic and inorganic materials. Cleaning does not kill microorganisms and a subsequent disinfection or sterilization process might be necessary to render the item safe for next use.”

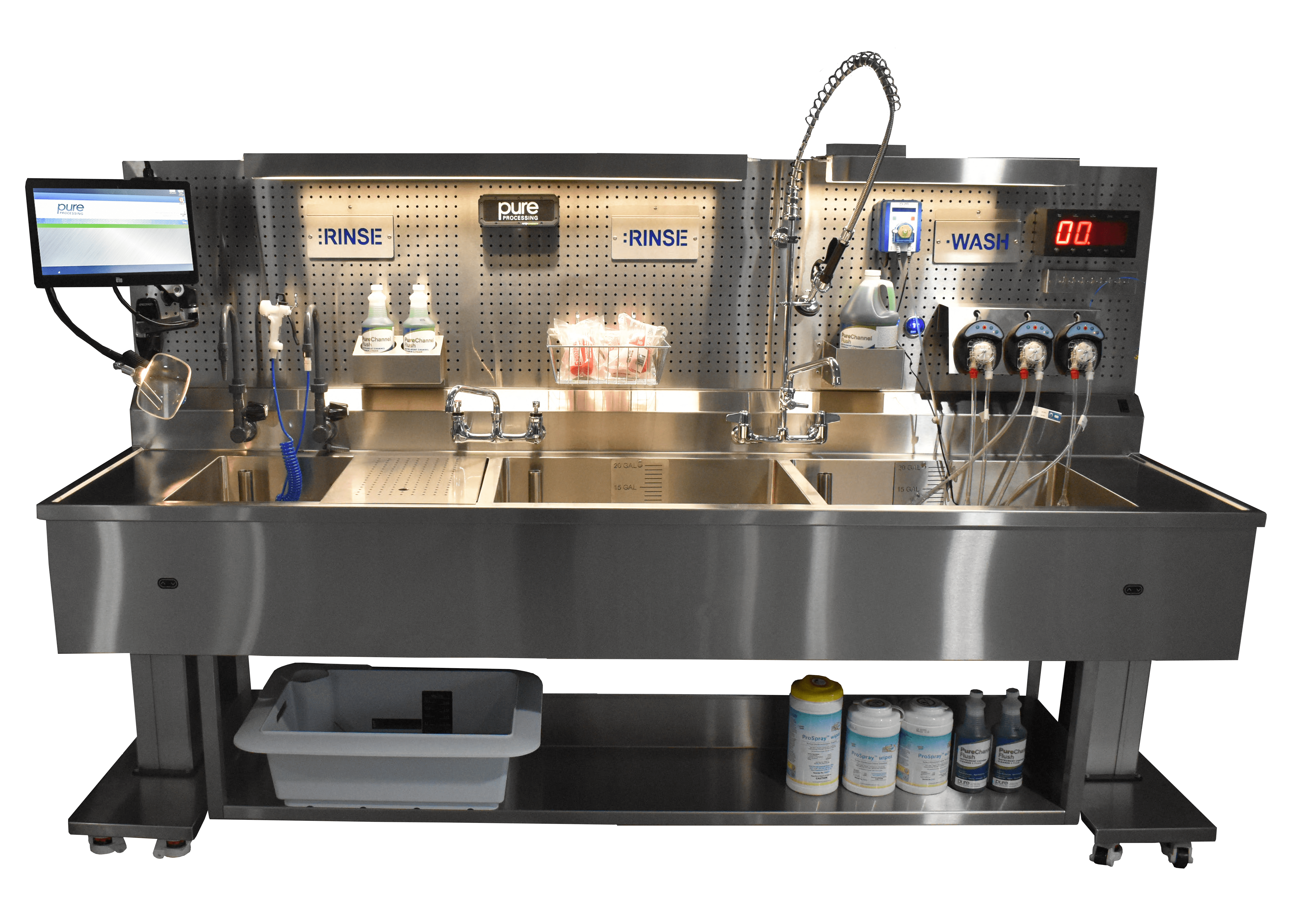

When it comes to effective manual cleaning, three foundational elements set the stage for successful outcomes: Flushing, Brushing, and Chemistries—the “F-B-C’s” of clean.

F is for Flushing

Flushing is the cornerstone of effective cleaning for surgical lumened devices. Copious, IFU-compliant flushing of every channel is essential, as incomplete flushing leaves soil and residual bioburden that impede high-level disinfection (HLD) or sterilization. These residues can even enable biofilm formation, which protects microorganisms from removal and eradication.

Biofilm is a tightly bound community of microorganisms encased in a protective matrix that adheres to instrument surfaces. Once established, biofilm acts like a biological shield—making it extremely resistant to detergents, disinfectants, and even sterilization processes. When biofilm remains on surgical instruments, the consequences are serious: increased infection risk, delayed healing, surgical site infections, and cross-contamination between patients. Furthermore, biofilm can accelerate corrosion and instrument damage, shortening device life and complicating visual inspection. Preventing biofilm through thorough flushing and timely cleaning is therefore not just a best practice—it’s a patient safety imperative.

Surgical device design adds layers of complexity to cleaning processes. Modern instrumentation is increasingly intricate, with tight tolerances, multi-material construction, and integrated technology that all contribute to cleaning challenges. Some of the most common

obstacles include:

obstacles include:

- Articulation joints that trap blood and tissue deep within hinge points or pivoting areas

- Cables and pulleys in robotic or powered instruments, which limit accessibility for brushes and flushing adapters

- Extremely narrow lumens, such as those in microsurgical and ophthalmic instruments, where fluid flow can be easily restricted

- Rough or textured surfaces that can harbor microscopic debris, making complete soil removal more difficult

- Hidden or nested components, including removable valves, seals, and tips that must be disassembled for cleaning but are sometimes missed

- Mixed materials (e.g., stainless steel combined with polymers or electronics) that each require different handling or chemistry compatibility

- Instruments which cannot be disassembled, causing debris to go unnoticed or to hide.

Copious, directed flushing helps combat these design challenges and ensures fluid reaches every internal surface. As ANSI/AAMI ST79 (Section 7.1) notes:

“Thoroughly flushing lumens helps ensure complete surface contact with the solution.”

Similarly, ANSI/AAMI ST91 (Sections 7.6 & 7.6.j) states:

“Flush all channels according to the endoscope manufacturer’s written IFU… verify that solution flows through each lumen… flush with water of the specified type, volume and pressure.”

Flushing isn’t only a step at the manual cleaning sink—it begins at the point of use. According to ANSI/AAMI ST91 (Sections 7.1 & 7.6):

“Prompt point-of-use flushing reduces the chance of soils drying, reduces biofilm formation risk, and is required to make subsequent HLD/sterilization effective.”

Whether performed immediately after use or during manual reprocessing, thorough and compliant flushing is the first critical step toward a clean instrument.

B is for Brushing

Mechanical action through brushing physically dislodges soils from surfaces and lumens and is required until no visible debris remains. Brushing must be performed with IFU-specified brush types, sizes, and techniques, such as keeping lumens submerged during brushing, to ensure complete contact and coverage.

Effective brushing isn’t just important for endoscope outcomes. As the earlier Ofstead study highlighted, retained debris within shavers and suctions demonstrates that all lumened instruments carry risk when brushing practices vary. Variances can emerge from differences in brush size, brush length, and the reuse or replacement frequency of brushes. If reusable brushes are not adequately decontaminated or replaced when worn, cleaning effectiveness declines rapidly.

Additionally, while many technicians brush until the brush emerges free of visible soil, this practice alone may not account for residual biological matter invisible to the naked eye. Consistency and adherence to IFUs are essential to minimize process variation and ensure optimal outcomes.

For guidance on effective brushing practices, ANSI/AAMI ST91 (Section 7.6) specifies:

“Brush accessible channels (e.g., the instrument/suction channel) according to the endoscope manufacturer’s written IFU until there is no visible debris and for the length of time specified. Use brushes of the length, width, and material specified by the endoscope manufacturer’s written IFU. Follow the brushing technique specified in the endoscope manufacturer’s written IFU to clean the endoscope, keeping the endoscope immersed at all times.”

Brushing is both a science and a skill—requiring precision, compliance, and quality control.

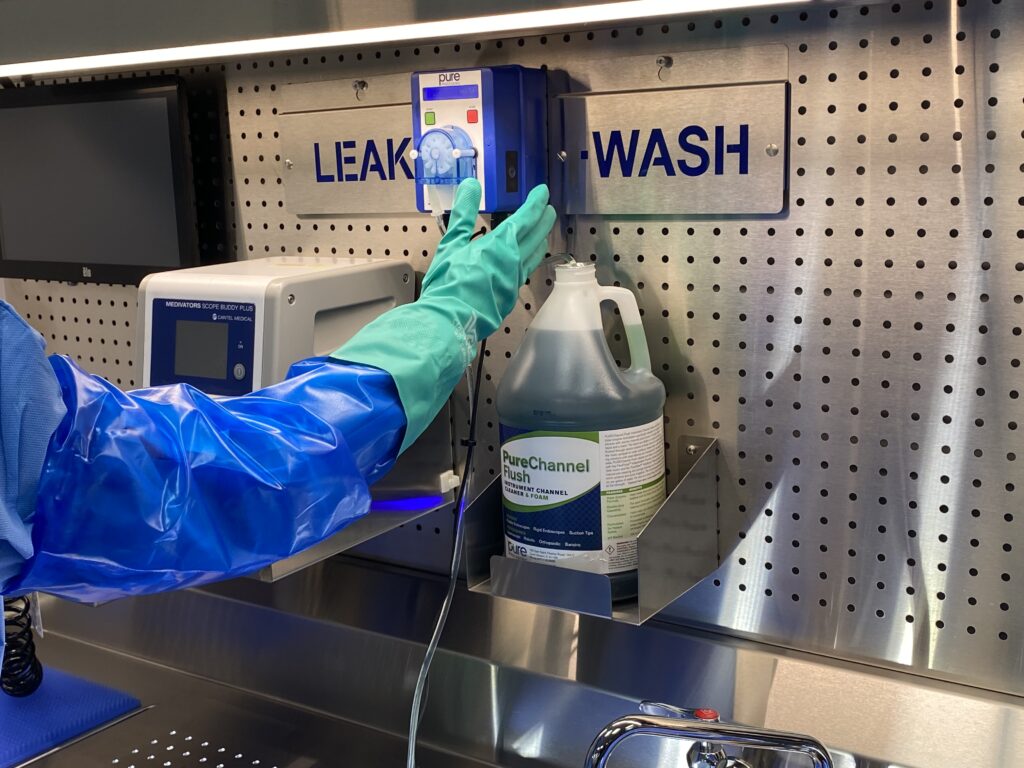

C is for Chemistries

The third foundational element in manual cleaning is the appropriate use of chemistries. Detergents and disinfectants used in instrument reprocessing are specialized formulations designed for medical applications. These chemistries must be used at the concentration, temperature, and contact time specified by both the detergent manufacturer and the device IFU.

Failure to properly dilute or rinse these solutions can result in residues that harm patients, damage instruments, or interfere with subsequent disinfection and sterilization.

‘Human’ bioburden—composed of complex organic materials like blood, mucus, and tissue—poses unique cleaning challenges. Protein denaturation, for example, can cause soils to adhere more tightly to surfaces, making effective chemistries essential to the manual cleaning arsenal. Equipping staff with the training and knowledge of how chemistries combat denaturation, for example, empowers and enhances outcomes.

The importance of chemistries also connects to the prevention and management of biofilm, a formidable adversary in the reprocessing world. As defined in ANSI/AAMI ST79:2017 (Section 3.1):

“Biofilm consists of an accumulated biomass of bacteria and extracellular material that is tightly adhered to a surface and cannot be removed easily. Biofilm has the effect of protecting microorganisms from attempts to remove them by ordinary cleaning methods used in the sterile processing area and of preventing antimicrobial agents, such as sterilants, disinfectants, and antibiotics, from reaching the microbial cells.”

Understanding and properly using validated cleaning chemistries are key defenses against these risks and essential to achieving consistent, verifiable cleaning outcomes.

Flushing, brushing, and chemistry use are the foundations of effective outcomes in manual cleaning. The complexity of the instruments we clean in sterile processing demands that these three activities be robust, validated, and repeatable.

Without effective and standardized processes, variability in these foundational steps can introduce risk, reprocessing errors, and real-world negative outcomes for patients.

However, with strong awareness, adherence to standards, and continuous education around these decontamination essentials, sterile processing professionals are better equipped to achieve safe, consistent, and optimal patient outcomes—the ultimate goal of every reprocessing department.

Looking for ways to improve & practice your F-B-C’s? Download our white paper which includes a checklist of tools and materials to check are in place for optimal manual cleaning outcomes!

Works Cited

- Ofstead, C.L., et al. (2024). Study on cleaning outcomes and borescope inspection of surgical instruments.

- ANSI/AAMI ST79:2017. Comprehensive guide to steam sterilization and sterility assurance in health care facilities. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI).

- ANSI/AAMI ST91:2021. Flexible and semi-rigid endoscope processing in health care facilities. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI).